Clones Lace

In the 1901 census of Ireland form A, many young women in the Clones area entered their occupation as “lace maker” “crocheter”, “crochet-maker”, “lace-joiner” or “lace buyer”. The townland of Aghadrumsee had five women employed in this way, Killyfole had five, Loughgare had six and Drumaa and Dernawilt each had seven . Nearly every townland around Killyfole Lough had at least one woman who gave her occupation as part of the Clones lace-making community.

The person responsible for introducing this industry to the area was Mrs Cassandra Hand, who was the wife of the then Rector of Clones Parish Church. Mrs Hand employed an expert teacher, arranged classes and organised the sale of the finished lace. The craft was introduced in post famine years as a way of making money and it did not involve much expenditure on the part of the craftswoman. The only materials needed were a crochet hook and some thread. The equipment took up little space and the women could work anywhere in the home.

The local women reflected their surroundings in the lace with motifs of shamrocks, roses, harps ferns, thistles, marigolds, cartwheels and many others, joined by the distinctive Clones Knot, which was a tiny ball made by turning the hook about a dozen times around the thread. A girl would become expert at a particular motif and would have an amount to sell each market day. The crochet buyer would take the motifs to another lace-maker who would join them with others according to what the buyer could sell. In some families, both stages were worked, the younger girls doing the motifs and the mother or elder sister joining and finishing and in some cases selling directly to the retailer.

Clones lace making was a lucrative business venture. Women from this area supplied lace for markets in Ireland, London, Europe and as far away as America.

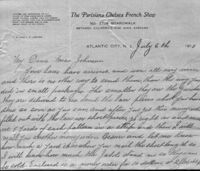

There are letters written to a local woman who was dealing directly with a shop in Palm Beach, U.S.A. By 1910 Clones was the most important centre for this type of lace. Royalty and gentry worldwide wore the lace. In the grand houses of the period, lace was also used for trimming the caps and aprons of the upper maidservants, and the vast quantities of table and bed linen. Sometimes, some of the lace was worn by the worker’s family. The Aghadrumsee School photo of 1907 shows several girls wearing lace collars on dark dresses.

There were side effects to working at lace. Crocheting was blamed for causing eye-strain and in some cases bringing on Tuberculosis. Elizabeth Johnston (Carneyholme) remembers as an eight year old finding a crochet hook and thread in the house and asking her mother to teach her to crochet. Her father took the materials from her and laid down the law, “No daughter of mine will poke her eyes out crocheting” and he threw the thread and hook into the fire.

After the First World War, fashions changed and the market for Clones Lace declined but lace making and sewing had been a family tradition, passed down from mother daughter. Mrs Eileen Johnston remembers her mother sewing, “She could cut a thing out of her head, I don’t know how she could do it!

I watched her and that’s how I picked it up. There were no patterns in her day.” One of Eileen’s first commissions was to make a dress for a friend. “I remember it was a pink satin crepe with short sleeves and a round collar. I sewed it all up by hand, back-stitching every seam. She wore it to all the dances. I got half-a-crown for making it. I was delighted.” Later Eileen had the benefit of paper patterns and a sewing machine but she never went to any dress making classes. Eileen made a blue suit for her wedding outfit and a pink suit for her bridesmaid, her sister Violet.

Today, people pay high prices for hand made, original clothing. Hand crafts like Clones lace or sewing are only known by a few women rather than, like it was a century ago, being many a woman’s source of income.